Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, Tokyo, Japan

Tokyo, Seoul, Taipei, X’ian, Beijing – these were the hotspots of women’s history on my trip to Asia in autumn 2019: six women’s museums in 3 or 4 countries (depending on your political attitude towards Taiwan – is it a part of China or an independant country?).

In this blog I will concentrate on three museums that deal with a topic that was not well known by me before – the socalled ‘comfort women & comfort stations’. These terms relate to the war crimes committed by the Japanese military. Thousands of women were forced to work as prostitutes during Japan’s invasion in the Asian-Pacific-region during the 20th century.

Highly irritated about these harmless sounding, euphemistic terms like ‘comfort women’and ‘comfort stations’ referring to a forced system of prostitution, I learn that these notions were made up and used by the Japanese military itself. That´s why they are still used as historic labels. As in literature I will set these special expressions under half quotation marks. Despite of this I hardly get used to them because they are hiding the facts and deceiving from brutality that was used. The more I get to know about the system the more I am outraged about the words. It makes sense that the perpetrators used them to play down the brutal offences and make them bearable for themselves. For me its a perfect example for exercising power with the means of languages.

Short introduction: What are ‘comfort stations’ ?

By running the socalled ‘comfort stations’ the Japanese government wanted to avoid that their soldiers rape women of the occupied countries. It was not for sparing women. There was the fear that the soldiers could be infected by sexual transmitted deseases and as a consequence, weaken the strength of the army. In the socalled ‘comfort stations’ women were steadily under medical control. This was not the only advantage. The problem of a pregnant woman was solved easily – she was forced to abortion. Not to forget that the soldiers should be provided with a pleasant way of being relieved of their sexual desires. Again and again I am bewildered and shocked how man take it for granted that we, the women of this world, are responsible for their sexual cravings – as would it be our natural duty towards them. If necessary they just go for buying it or they force someone to do it.

The Japanese military built the camps, run and maintained them. There were three types of camps: the ones, directly run by the military; others that were privately run under a military contract and privately run ones. Especially the third category is used by the Japanese government to refuse its guilt and responsibility. Many times the rape camps were set up in houses, schools or temples, because many rooms were needed. Sometimes tents were set up on battle fields. Also caves and bunkers were used as ‘comfort stations’. Women who had to stay in the camps, worked during the day (washing, cooking…) and during the nights they had to serve the soldiers. Others were forced to follow the troops or were brought to military camps at the front line.

We don’t want to hear any longer, that women are protected by war. No, they are raped by war.

Lida Gustava Heymann (1868 – 1943), German feminist, pacifist, author, 1915

Commemorating culture in the perpetrating state

Do you remember Sofia Coppola’s movie “Lost in Translation”? A kind of this alien or forlorn feeling of the protagonists in the film might come up when you realize that you are searching for an address within the biggest metropolitan area of the world – Tokyo and its 38 million inhabitants. At first sight it feels like a small adventure. And, surprisingly, it`s an address without any street´s name:

Women´s Active Museum on War and Peace (WAM)

AVACO Bldg 2F, 2-3-18,

Nishi-Waseda, Shinjuku

TOKYO

Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, WAM, Tokyo, Japan

Grown up as an “analog native” I try to find my way by looking at the city map. Step by step I get oriented. I realize that “Shinjuku” is the district I have to head for and that there exists a subway station, named “Nishi-Waseda”. Then Google helps me to find the exact route to go there. It even lets me know which exit I have to use when leaving the subway system for a short footpath to reach the museum. Without digital help I hardly would have found the narrow alley in which the AVACO Building 2F is situated.

Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, WAM, Tokyo, Japan

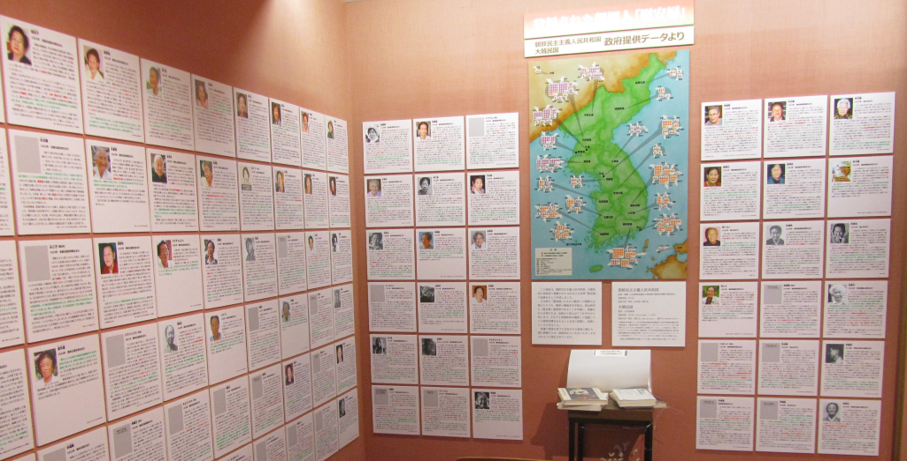

When you enter the first room of the museum you look at many photos of women displayed on the walls. Mina Watanabe, the director of the museum, explains: “These are portraits of 179 women from 10 countries: North- and South Korea, Taiwan, China, Japan, The Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, East Timor, Burma (nowadays:Myanmar) and Vietnam. These women had to work as sex slaves for the Japanese military till Japan´s capitulation after the 2nd World War. They agreed to make their photos public. Behind this small number of survivors presented here there exist thousands of women who either didn’t survive the war or the post-war period or those, who are still – out of personal reasons – silent on their fate. But they also shouldn’t be forgotten. Do you see the white left-over space at the end of the portrait-gallery on the wall? It refers to their existence. A white flower put to the portrait means that this woman has already passed away. These photos here on the opposite wall give evidence of very courageous women. They dared as the first ones of their countries to file a lawsuit against the Japanese government.” Not yet finished with her explanations, two visitors are interrupting our talk, quite unusual and impolite in this country with its strict codes of behaviour – a gentleman introducing himself as correspondent, accompanied by a lady. Even with their first remarks they announce that they don’t agree with the full contents displayed in the museum. During the time Mina guides me through the museum they show up from time to time, asking questions, making comments or arguing against the contents displayed. Mina time and again has to discuss with them. Although the United Nations ‘comfort women’ have recognized as “sex slaves” and ‘comfort stations’ as “rape camps”, Mina still has to justify why she uses these terms in the texts. For “our” visitors these women worked as prostitutes voluntarily. How come?

After Japan’s occupation of Korea its inhabitants got poorer and poorer. For many women the only chance to survive was to work as prostitutes, as ‘comfort women’. That´s why Japan speaks of them as “volunteers”. Questions arise: Is there a difference between ‘comfort women’and the prostitution business? Who is not willed to make a distinction between both? Where begins / ends the voluntariness in case of prostitution? Especially the last question is highly and controversely discussed even nowadays, in a “time of sex work as a job as any other”. For me it seems, that with focussing on and discussing about voluntariness the Japanese government wants to decive from the fact, that many women were kidnapped, threatened and brought by force to the rape camps. Others were promised to get a good job, in the end they found themselves in a rape camp.

Mina Watanabe, director of Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, WAM, Tokyo, Japan

I knew beforehand that the women´s museum of Tokyo doesn´t face full acceptance in Japan, mainly by people affiliated with right wing politics. During my visit I experience how “hot” the issue for some Japanese still is and how hard your life can be if you critically shed light on a dishonourable part of history. Up to now no prime minister of the country took over responsibility for the war crimes done on women.

In the second room of the museum a special exhibition is on display: “Listening to Korean ‘comfort women’: Effort to Take Responsibility for Japan’s Colonialsim” (1910 – 1945).

“A lot of research work was necessary to make this exhibition happen. In the end we received a lot of data from the governments of North and South Korea. From many of the former sex slaves we only know because they needed social subsidy and aid to make their living. For this reason they had to register and confess that they once were ‘comfort women’. With these 183 fotos and short biografies we want to remember the fate of these women”, Mina explains. 500 words should tell about the live of each woman – no matter, was she a political activist or a silent woman. It`s touching to look at the many white spots in the stories and to get to know that from so many of them nothing more can be figured out.

Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, WAM, Tokyo, Japan

Room 3 of the museum provides on a multicoloured strip of paper a chronological general view of the years between 1875 – 2018. The time relating to the years before Japanese colonialism shows the way the military prostitution system came into being. On a pink strip you may figure out how the Japanese Colonial Government exported the rape system to Korea. The time after the Second World War is provided on a yellow strip. It is of importance because colonialism towards Korean women who continued to live in Japan with the historical background of having been ‘comfort women’ before, didn’t end after 1945. In addition, it refers to the fact that in the 1960ies and 1970ies Japanese man went to Korea for sex tourism.

Before leaving the museum I pass by a series of photos showing men in uniforms. They are exhibited here because they are the ones responsible for the setting up of the compulsory prostitution system. Its very important to make the perpetrators visible and to be able to look into their faces. They should at least know that they cannot longer hide their identities. As raping women still is a fact in every war on this planet they should at least know that they are prosecuted and more and more made responsible for their cruelties.

Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, WAM, Tokyo, Japan

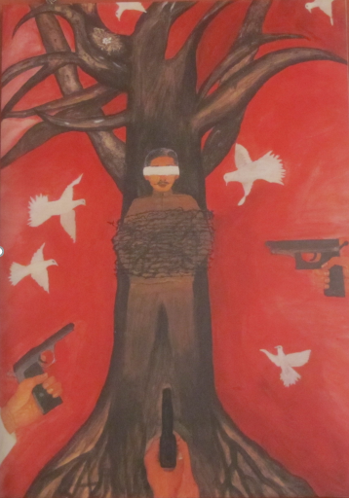

While looking into these faces I remember a painting I had seen before in the exhibition. It was painted by Kang Duk-Kyung, a former ‘comfort woman’. She names it “Punish the Responsible”. Thus I go back to have a closer look at it.

Kang Duk-Kyung: Punish the Responsible

It’s very powerful in it’s message. Considering the fact that Japan is – even 75 years after the end of the war and the rape camps – not willed to take over responsibility or to apologize for the brutal behaviour of its military this painting not only conveys a personal story of a woman, it also is of great political moment.

(I will meet Kang Duk-Kyung again in the Korean ‘comfort women’museum in Seoul, called: War & Women’s Human Rights Museum)

At the end I want to present a woman very important for the museum itself and to the women in the world: Yayori Matsui (1934 – 2002). She was a well known journalist and a feminist activist. For the museum she is important because she had the idea of establishing a women’s museum in Tokyo. She became famous all over the globe because she proposed the idea of installing the “Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal”.

The only way to fight against globalization is by globalizing our solidarity.

Yayori Matsui (1934 – 2002)

To be as active as the founder seems to be a principle of the WAM = Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, its name already referring to it. It provides a variety of activities, like symposiums, seminars, workshops besides its intense research work on Japan`s military sexual slavery system. The museum is in contact and works together with many organisations around the world. With all these activities it aims to fight against war crimes done on women and to make them visible.

Marianne Wimmer, collector of women’s museums

In 2015 Marianne Wimmer from Austria had an idea: She wanted to be the first woman to visit all the women’s museums in the world. She did not loose much time, and started her visits in women’s museums around the world. In a series of articles here on this platform she will tell us about her experiences.

Here you can read her first article.

Coming up next: War & Women’s Human Rights Museum, Seoul, South Korea

Here you can read this article in German.

Marianne Wimmer