Over more than a decade of activity, Black Brazil Art (BBA) has established itself as an independent institution dedicated to promoting, disseminating, and reflecting on the artistic production of Black artists in Brazil and in dialogue with the African diaspora. Founded in a country of continental dimensions, where geographic distances often hinder the circulation of artists and their works, BBA committed from the outset to building bridges: connecting trajectories, facilitating exchanges, and creating a common space to reflect on the role of art in Brazilian society and beyond its borders.

The project was born from a simple yet radical gesture: bringing together artists, researchers, curators, and collectives to engage in open conversations about Black participation in the construction of Brazil. This starting point proved fertile, as the national history is marked by the presence of African peoples and their descendants, but also by the systematic silencing of their contributions. In this context, BBA operates as a space of symbolic repair and visibility, bringing to the fore practices, knowledge, and narratives historically marginalized, invisibilized, or appropriated. BBA also positions itself as a space of aesthetic insurgency. This is guerrilla art: it enforces the resistance of knowledge and memories of Indigenous peoples, reaffirming the importance of a decolonial critical perspective in cultural production. In this sense, Nego Bispo’s reflection on the centrality of the body, memory, and ancestry as political and aesthetic practice serves as a reference for developing projects that not only preserve traditions but also challenge established power and colonial hegemony.

Over more than ten years, the institution has consolidated programs of residencies, formative gatherings, workshops, exhibitions, and, more recently, the Black Brazil Art Biennial — an international platform that expands dialogues and connects artists from diverse backgrounds. This trajectory demonstrates that BBA is not merely an exhibition space, but a territory of collective elaboration, where artistic practice merges with research, writing, and critical thought. To foster dialogues of insurgent art within colonial critique, BBA recognizes the necessity of bringing together non-Black artists as well, allowing them to become aware of structures of power, privilege, and erasure, and to engage in collective reflection processes.

Photo 1

Non-Fungible Narratives in the Brazilian Experience

Considering the conceptual proposal of “non-fungible narratives,” as formulated by the research group at NSCAD University, it becomes evident that Brazil is fertile ground for this debate. The notion of a non-fungible narrative refers to that which resists substitution, which cannot be commodified or forgotten, remaining alive even after centuries of colonial violence, slavery, and attempts at cultural erasure. In Brazil, these narratives manifest in everyday practices, religious symbols, forms of sociability, and modes of artistic production that carry African ancestral memory, while also intertwining with Indigenous influences and the unique dynamics of each region of the country.

African presence in Brazil was not limited to demographic numbers — although massive — but established deep cultural matrices. In language, cuisine, musical rhythms, dance, dress, and religious practices, we find marks of this ancestry that resisted colonial logic. On the contrary, these marks reinvented themselves, disseminated, and became foundational to the identity of millions of Brazilians. Attempts at erasure — whether through the criminalization of African-derived religions or the stigmatization of Black cultural practices — reveal how the non-fungibility of these narratives challenges colonial structures, as within them lies a power of continuity and collective affirmation.

Among the most expressive examples are belief systems such as Candomblé and Umbanda, which survived persecution and preserve symbols, songs, and gestures of resistance. The beating of the atabaque, the presence of orixás, offering rituals, and circular dances are more than spiritual practices: they are non-fungible narratives, carrying ancestral memories active in the present. Similarly, elements of diaspora cuisine — acarajé, vatapá, feijoada — express modes of resistance perpetuated through taste, communal gatherings, and oral transmission. These narratives are not confined to tradition; they permeate contemporary artistic production. Artists participating in BBA residencies explore these elements as raw material for creation. Through painting, photography, installation, or performance, they revisit ancestral symbols and place them in dialogue with contemporary issues such as structural racism, migration, gender, and environmental concerns. In this process, BBA acts as a catalyst, providing a safe space for developing works that challenge market pressures and exclusionary institutions.

The Brazilian experience is marked by complex tensions between African, Indigenous, and European heritage. Therefore, when discussing practices that resist erasure, we are not only referring to the survival of African matrices but also to how they intertwine with other knowledge systems. Indigenous dance incorporated into Afro-diasporic rituals or the use of African symbols by non-Black artists reveals a crossroads that challenges simplistic notions of belonging and identity.

In this context, BBA positions itself as a mediator: a space where multiple cultural layers are recognized, problematized, and celebrated. Non-fungible narratives in Brazil are simultaneously resistance and invention, memory and future, root and rhizome. It is at this intersection that the institution builds its formative role and international relevance, highlighting an insurgent artistic practice, a cultural guerrilla approach that reaffirms ancestral knowledge and enforces decolonial critical reflection.

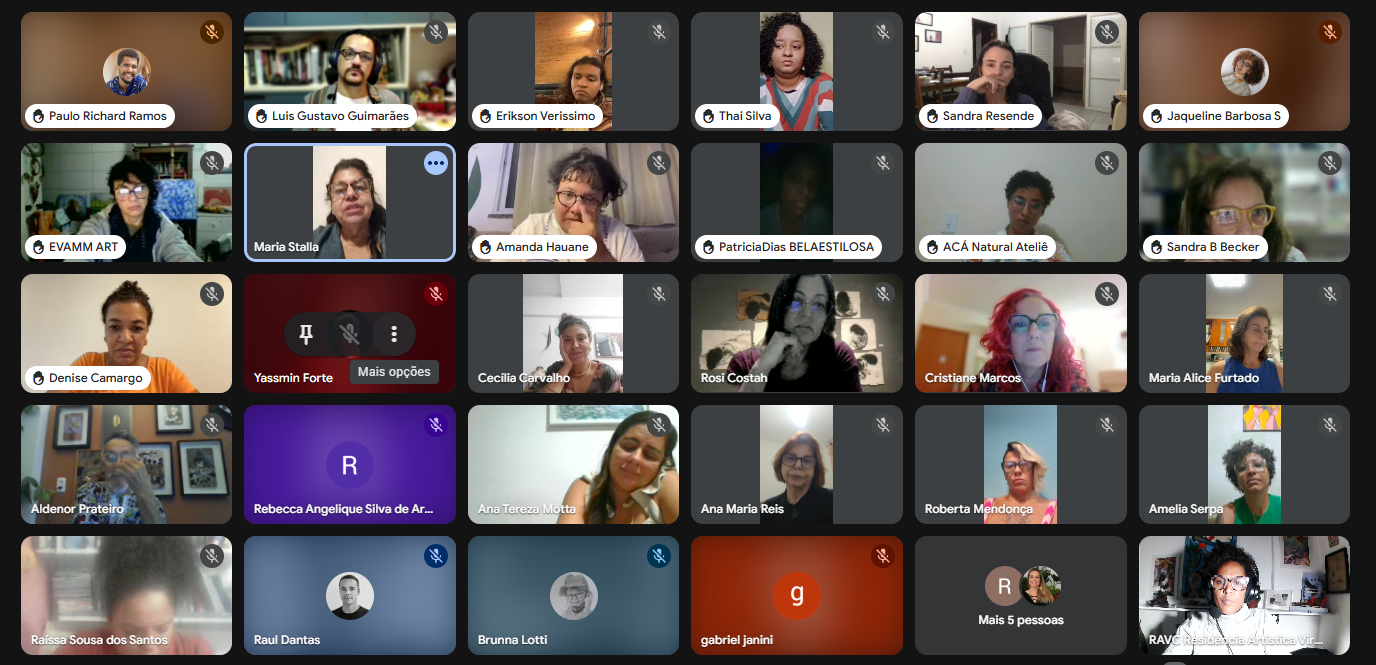

Photo 2

Residencies as Formative Laboratories

From its earliest years, Black Brazil Art recognized that creating exhibition platforms alone was insufficient: it was essential to invest in formative processes that encouraged artists to critically reflect on their practices, engage with diverse trajectories, and recover symbols and narratives capable of sustaining their creations. Thus, the artistic residencies organized by the institution emerged, conceived not merely as periods of production, but as true laboratories of critical and insurgent thinking.

These residencies function as spaces of displacement. The artist is invited to step out of their routine and everyday geography to immerse themselves in a collective environment where exchange becomes a central element. More than producing finished works, the objective is to experiment, research, and coexist, building bridges between personal and collective memories. In this sense, the residency is both an artistic and a political exercise: to resist is also to create in community, reinforcing art as a practice of cultural guerrilla capable of confronting dominant colonial narratives.

During these encounters, different trajectories intersect: Black artists from various regions of Brazil — from the northeastern hinterlands to urban peripheries in the south — coexist with Indigenous, white, and artists of other ancestries, all immersed in processes of sharing. This diversity is extremely powerful, allowing African ancestry to always be in dialogue with other cultural matrices that compose Brazil. These are moments in which family histories emerge, songs learned from grandparents, everyday religious symbols, and reflections on racism, inequality, gender, and territory.

The intertwining of these memories generates a fertile ground for constructing the so-called non-fungible narratives. Each artist carries something irreplaceable: a memory, a mode of making, a symbolic repertoire. By sharing these experiences, they reaffirm their identities and construct collective narratives that resist erasure and oblivion. The residency thus becomes a space for the continuous updating of ancestry, transforming art into a tool of resistance and cultural insurgency.

A recurring example is the dialogue around Afro-diasporic religiosity. Many artists incorporate symbols from Candomblé, Umbanda, or other Afro-diasporic traditions as central elements of their works. African symbols, such as adinkras, also appear frequently. These elements carry histories of persecution, resistance, and reinvention; revisited in contemporary practices, they become non-fungible, affirming the presence and vitality of communities that survived colonialism and slavery. Other artists incorporate Indigenous memories or create hybrid symbols — crosses, ribbons, braids, painted bodies — expressing Brazilian cultural syncretism and the complexity of its historical formation.

Beyond symbols, modes of making also emerge as non-fungible narratives. The use of embroidery, ceramics, basketry, or oral traditions — practices often inherited from families or traditional communities — gains new life when incorporated into contemporary visual arts. These modes of making are not mere techniques; they are living repertoires that connect contemporary art to the heritage of the land and Indigenous peoples, reaffirming the creative power of the artists and situating their works within a broader field of collective memory.

BBA residencies, therefore, do not constitute isolated moments but stages of a continuous process of formation and resistance. Each encounter accumulates experiences and knowledge that artists carry forward into their works, returning to the institution in the form of exhibitions, publications, or debates. It is through this formative cycle that BBA develops the Black Brazil Art Biennial, a project nurtured by the experiences lived in residencies and reinforcing the insurgent and guerrilla character of diasporic art.

Photo 3

From Residency to Biennial: An Independent Platform

The Black Brazil Art Biennial emerges as a natural extension of these experiences. If in the residencies artists immerse themselves in processes of collective investigation, at the biennial they have the opportunity to present the results of this research to a broader public, in dialogue with other artistic contexts. It is a movement from inside out: from intimate exchanges among artists to the international public stage.

The choice to structure an independent biennial was intentional. The Brazilian institutional landscape still presents numerous barriers to the visibility of Black, Indigenous, and peripheral artists. Major art institutions remain guided by Eurocentric narratives and market logics that tend to exclude dissident, community-based, or insurgent practices. Creating an independent biennial meant asserting autonomy and building a platform capable of hosting narratives that find no space in traditional circuits.

The 2024 edition, held in Rio de Janeiro, marked a milestone in this trajectory. In addition to gathering artists from different regions of Brazil, the biennial opened space for Canadian artists, fostering a transnational dialogue. This experience reinforced the idea that non-fungible narratives are not limited to local contexts but can be shared and recognized across different geographies of the Black diaspora. The encounter between Brazilian and Canadian artists demonstrated how symbols, memories, and modes of making traverse oceans and resonate in distant realities.

The presence of foreign artists also highlighted BBA’s role as a global mediator. By connecting experiences from Brazil with those of Canadá and other regions, the institution contributes to constructing a transatlantic field of resistance. This international dimension does not erase local specificities; on the contrary, it valorizes them, showing that what is non-fungible in one context can dialogue with what is non-fungible in another, creating networks of solidarity and shared memory.

In this way, the Black Brazil Art Biennial is not merely an exhibition event. It is the culmination of a formative process that begins in residencies and expands to the world, affirming the place of Afro-diasporic and Indigenous art in the contemporary scene, while proposing new ways of thinking about history and the future as insurgent and cultural guerrilla practice.

Photo 4

Writing as Resistance and Collective Practice

If, in the residencies of Black Brazil Art, symbols, modes of making, and collective memories emerge as non-fungible narratives, writing occupies an equally fundamental place in this process. More than a mere documentary record, writing is understood as an act of resistance—a practice that inscribes on paper—and increasingly on digital media—that which has historically been silenced or marginalized. It is grounded in collective listening: the written record arises from dialogue among artists, curators, and researchers, and is built through the constant exchange of experiences and memories.

In the Brazilian context, writing has always been fraught with tension. For centuries, literacy was a privilege of white elites, while enslaved Black people and their descendants were systematically denied access to reading and textual production. This exclusion created an imagination in which the written word appeared as a forbidden territory, controlled by colonial power. Yet, alongside this process, oralized forms of writing flourished: songs, prayers, proverbs, narratives transmitted in capoeira circles, Candomblé terreiros, or community assemblies. These expressions constituted living libraries that escaped colonial logic and preserved knowledge that could not fit in books or official documents.

By reclaiming this tradition, BBA understands writing in an expanded and plural sense. Critical texts, process journals, zines, portfolios, catalogs, manifestos, and audiovisual records incorporating oral traditions are all considered forms of writing. This expansion is essential, as it allows artists who may not identify with academic writing to produce legitimate narratives about their own practice. Writing thus becomes a tool for autonomy, identity affirmation, and cultural insurgency, contributing to the construction of a collective knowledge that resists colonial and erasure structures.

During residencies, artists are encouraged to maintain process journals, recording reflections, drawings, scattered phrases, song fragments, or personal memories. These journals are not evaluated as finished works but as testimonies of trajectories in formation. At the end of the residency, many of these records are shared collectively, giving rise to experimental publications—collective catalogs, artist books, or zines. These products function as capsules of memory, preserving lived experiences and creating archives that resist forgetting, reinforcing the idea that collective memory is insurgent and active in the present.

A central aspect of these practices is their non-commercializable nature. Unlike works that circulate in the art market, writing in journals, zines, or process diaries does not easily submit to market logic. It circulates hand-to-hand, in small editions, in community contexts. In this dimension, writing becomes a non-fungible narrative: a way of asserting that it cannot be reduced to exchange value, resisting fungibility and remaining alive in collective experience.

Writing also plays a crucial role in the construction of the Black Brazil Art Biennial. From its first edition, the biennial has not limited itself to gathering works in exhibition spaces but has sought to generate critical documentation that circulates beyond the event. Catalogs, dossiers, curatorial texts, and artist interviews constitute an archive that amplifies the biennial’s impact and ensures that experiences are not lost after the exhibitions conclude. More than memory, these records function as pedagogical tools, accessed by students, teachers, and researchers in different contexts, creating new spaces of listening and collective learning.

By investing in writing as a collective practice, BBA inserts itself into a broader tradition of the Black diaspora, which has used the word as resistance for centuries. From 19th-century published testimonies of formerly enslaved people to the oral narratives of African griots, and from 20th-century manifestos by Black artists and intellectuals, we find a constellation of experiences in which writing—oral or textual—asserts humanity, records memory, and proposes futures. BBA’s work directly dialogues with this genealogy, connecting the present to the memory of the diaspora and the shared struggles of Indigenous peoples and Black communities worldwide.

Another relevant aspect is the articulation between writing and digital technology. In recent years, BBA has explored resources such as blogs, online magazines, PDF catalogs, and multimedia experiences in video and audio. This diversification broadens access and democratizes circulation, reaching audiences who might not have contact with print publications. At the same time, it reinforces that writing does not need to be linear or exclusively textual: it can be sonic, visual, and interactive. This openness allows us to think of writing as an expanded field, in tune with contemporary and insurgent artistic practices.

Within residencies and the biennial, collective writing also assumes a political role: producing documents that denounce inequalities, propose inclusive cultural policies, and affirm the right to memory. By bringing multiple voices into a single text, BBA creates a space of shared authorship that breaks with the idea of individual genius and values collective knowledge. This gesture is particularly important in a country where official history still tends to silence or marginalize Black and Indigenous contributions.

Therefore, when we speak of writing in the context of BBA, we are not referring only to academic texts or formal curatorial writing, but to a multiplicity of records that together compose a living archive of resistances. This archive is both memorial and prospective: it preserves lived experiences, projects possible futures, and sustains the continuity of non-fungible narratives. Collective listening is the foundation of this process: to write is, above all, to hear and be heard, to construct meaning together, and to strengthen the insurgent field of Afro-diasporic and Indigenous art.

Photo 5

Conclusion and Perspectives

Throughout this essay, we have explored different dimensions that structure the proposal of Black Brazil Art (BBA) and its work in the field of non-fungible narratives. We began with a reflection on how the notion of non-fungibility—originally inspired by debates in the digital economy but re-signified in a cultural and political key—allows us to understand experiences that cannot be reduced to market logic or substituted with equivalents. We have shown that, in Afro-diasporic art practices, memory, body, orality, and ancestry produce forms of expression that resist homogenization and affirm singular ways of existing.

Next, we highlighted how BBA, through its artistic residencies, creates privileged spaces for the emergence of these narratives. By bringing together artists from different regions, backgrounds, and trajectories, the residency functions as a collective laboratory, where symbols, affections, and memories are shared and reinvented. More than aesthetic experimentation, it is a pedagogical and insurgent process, in which each artist learns from others and from the community, building new languages that articulate experience, resistance, and creativity. Collective listening is the foundation of these processes, allowing artistic production to thrive on dialogue and diversity of knowledge, including among non-Black artists, fostering critical and decolonial awareness.

In the third stage, we reflected on writing as a practice of resistance and memory. We showed that, far from being restricted to academic records, the writing that emerges at BBA is multiple: process journals, zines, manifestos, collective catalogs, and digital records. This multiplicity ensures that memories are not lost and that historically silenced voices are preserved. Writing becomes a work in itself, a non-fungible and irreplaceable narrative because it carries marks of experience, orality, and collectivity.

We then reach the international dimension. By dialoguing with initiatives such as the Minorit’Art project at NSCAD University (Canada), BBA projects its actions into a global circuit of debates on diversity, inclusion, and cultural reparations. This dialogue demonstrates that the challenges faced by Black and Indigenous artists in Brazil resonate with struggles shared by other racialized communities while also expanding the circulation of non-fungible narratives, connecting local and transnational experiences of cultural resistance.

The culmination of this trajectory is the Black Biennial 2026, structured around the theme of the five skins, which invites reflection on body, identity, memory, territory, and ancestry. It engages with the work of Hundertwasser—who values multiplicity, the organic, and the re-signification of space—and the thought of Nego Bispo, who understands the body and memory as territories of aesthetic and political insurgency. This edition of the biennial brings together artists who participated in the residencies, presenting works that express the convergence of tradition, innovation, and resistance. Each work reflects individual trajectories but also participates in a collective gesture: the construction of a shared narrative that challenges colonial structures and reaffirms the potency of the African diaspora and Indigenous peoples.

Black Biennial 2026 demonstrates how residencies, collective listening, and writing converge to create an ecosystem of artistic-political production. By bringing the concepts of the five skins to the fore, the biennial proposes a sensitive map of the multiple layers of experience, body, and memory that compose Black and diasporic life in Brazil. The articulation between aesthetics and resistance is revealed in works that occupy both public and institutional spaces, where symbols, colors, textures, and hybrid languages produce unexpected encounters, reinforcing the cultural guerrilla practice that characterizes BBA’s work.

Ultimately, BBA demonstrates that its strength lies in its ability to articulate residency, writing, exhibition, and circulation within a single flow. This methodology allows artists to produce, document, and share non-fungible narratives, strengthening collective memory and raising awareness of historical inequalities. By inscribing Black and Indigenous art on the international horizon, BBA does not merely exhibit works—it builds bridges of critical and formative dialogue, fostering processes of social and cultural transformation.

To speak of non-fungible narratives in the context of BBA is, therefore, to affirm that certain dimensions of Black and diasporic life cannot be reduced to numbers or market equivalents. They are narratives of body, memory, and future, which resist colonial logic and expand through collective listening, insurgent writing, and collaborative artistic creation. Black Biennial 2026 represents the concrete outcome of this trajectory: a space of aesthetic, political, and pedagogical affirmation, where experiences accumulated in the residencies are translated into works, discourses, and practices capable of projecting new ways of existing, thinking, and resisting.

PATRICIA BRITO KNECHT

Independent curator, museologist, and art critic, she is the founder of the Bienal Black and the Shared Virtual Artistic Residency Program. She is a member of the Brazilian Association of Art Critics (ABCA), the International Association of Women’s Museums (AIWM), and the European Network of Brazilianists in Cultural Analysis (REBRAC). A contributor to the Itaú Cultural Encyclopedia, she has been featured on the Map of Black Curators in Brazil by the state of Rio Grande do Sul, through the Latin American Art Workers collective. In 2021, she was nominated for the Açorianos Award for the 1st BIENALBLACK. She is also the author of the novel Casa Grande SEM Senzala, published by BBA. Her curatorial practice is deeply engaged with decolonial perspectives, contemporary artistic practices, and transnational dialogues, seeking to expand the visibility of Afro-diasporic narratives within global art circuits.

Social mídia

Instagram/@ bienalblackbrazilart

PodCast/black-brazil-art

YouTube/@BlackBrazilArt

List of photos:

Photo 1 – (biennial black 1); Decolonial Critical Thinking in the Artistic Practices of Black Brazil Art; Non-Fungible Narratives in the Brazilian Experience

Photo 2 – (virtual residency class); Residencies as Formative Laboratories

Photo 3 – (biennial black 2); From Residency to Biennial: An Independent Platform

Photo 4 – (artists in conversation); Writing as Resistance and Collective Practice

Photo 5 – (exhibition Ingenuo e Primitivo, 2014); Conclusion and Perspectives