Join Marianne Wimmer on her journey through Cleveland, Ohio

We are leaving the historic grounds of the women’s suffrage movement in New York State to open a new chapter of women’s history. Along Lake Erie we drive to Cleveland, the second largest city of Ohio, where the fourth woman’s museum on our trip is waiting for us. It is located in a very special place, in the terminal building of the airport in downtown Cleveland. Burke Lakefront Airport right on Lake Erie and near the city center is mainly used by visitors of congresses, fairs, concerts, … or by those coming in by sport planes.

International Women’s Air & Space Museum

Burke Lakefront Airport

1501 North Marginal Road

Cleveland, OH 44114

www.iwasm.org

What do Icarus, Leonardo da Vinci, Otto & Gustav Lilienthal and the Wright Brothers have in common? Normally, they are the ones that come to our minds when we think of the beginnings of aviation. They stand for the first generation of pioneers in the field. Not to forget Charles Lindbergh, the first to cross the Atlantic Ocean in 1927 (New York – Paris 5 800 km). But what about his wife, Ann Morrow Lindbergh (1906 – 2001)? She as well was a pioneer in aviation and an author. Different from her husband she hardly ever is mentioned, although they undertook expeditions together and she gained several awards for her abilities in aviation and navigation. The history of aviation told to us is full of men and their achievements. No wonder, as we touch the field of engineering that by tradition is not part of girls’ common socialization.

“Keep your hands off, that is nothing for you!”

Who has not heard this warning directed at girls for centuries. You immediately knew that your sex was not seen as the gifted and talented one in the realm of technology. Prejudices like this evolved and – as I fear – still form our thinking about girls and boys. Even in the 3rd millennium women are rarely found in technological professions, despite a variety of programs, especially for girls, like “Girls Days” or “FIT” (=women in techniques), that want to awake girls’ interest in the field. It is a matter of fact that working as a technician goes hand in hand with earning good money, at least much more than in typical female jobs. And what is more important for a woman than being financially independent as the basis for a self-determined life? Strictly speaking, men working in technical branches may feel happy that the programs for girls don’t work because past experiences show: As soon as women enter a field of work, its reputation and its wages are decreasing. I guess, it’s time to think about the rating of jobs in a new way.

Despite the negative attitude women had to face in technology, they performed very well from the beginning of aviation. One just must be willing to search for them. And this is what the WASM (Women in Air & Space Museum) does. Again, I realize how important autonomous women’s museums are for making women’s achievements and contributions visible. It will even get more explicit later on in Washington, when we will visit the “National Air & Space Museum”. It is obvious that the original museum’s concept focused exclusively on men. Nowadays, no one can afford to neglect women totally, they are incorporated in exhibitions. A special exhibit dealt with Amelia Earhart and her pioneering role in aviation which I really appreciate. Compared to the presentation of Earhart the section of “Women Pilots” turned out as meager. All in all, only a few square meters of this huge museum are dedicated to women.

But let’s turn back to Cleveland.

Display cases with trophies, garment, photos, stamps, coins, documents,…. planes,………..At the beginning of my visit I am strolling through the exhibition hall to obtain a general view. It is impressive to read that a girl pilot has built and test flown this mini plane, exhibited her. I have never heard about girl pilots before.

Then I am attracted by the words “ Living & Working in Space”. Here I get basic information about life and work in space: about food, weightlessness, the 2 hours of daily training. If you follow the invitation: “Try to slip into the sleeping-bag”, you may pass (or not) your first test of skill. If you can’t make it here, without the condition of weightlessness, you never will make it to the moon?

And what’ s this cute object over there that looks like a toy and reminds me of my childhood? Looking at it I see myself as a little girl, having fun while “flying” through the air with a similar looking plane at a merry-go-round. It’ s a pity that you cannot jump into this attractive flight simulator to test it.

Now I switch over to the pioneers in aviation and aerospace. The stories of more than 6000 women are collected and presented in the museum – incredible. And they set up records, records, records! Under the category “the first woman” to…. you are fascinated by:

-

- Harriet Quimby: Americas first woman pilot (1911)

- Bessie Coleman: first African-American pilot (1921)

- Amelia Earhart: first woman to fly the Atlantic (1932)

- Conny Wolf: Americas first “Lady of Lighter-Than-Air, a balloonist, flew a Liberty Bell shaped balloon over Philadelphia; first woman to fly over the Alps in a balloon (1951). She holds 15 women’ s world records in ballooning

- the first American women astronauts (1978)

- Sally Ride: first woman in space (1983)

- Ruth Nicols: woman of records – the only woman that simultaneously held records in speed, distance and altitude as a pilot

Curious about these great “role models”, that demonstrate that women are not limited because of their sex? With their partly bold single flights and records they furnish evidence that women are able to accomplish technical top performances. What restrains us is not our sex but prejudices, skepticism and doubts towards us when we are raised, just because we are girls.

“I was annoyed from the start

by the attitude of doubt by the spectators

that I would never really make the flight.

This attitude made me more determined than ever to succeed.”

Harriet Quimby (1875 – 1912)

Amelia Earhart (1897 – 1937) always wanted to be honored and appreciated because of her achievements and not for her womanhood. In her childhood she behaved like a vigorous tomboy. As a young lady she did not give up her spirit of adventure. Volunteering in a Red Cross Hospital during the 1st World War she took care of hurt military pilots. Later on she engaged as a social worker in the poor areas of Boston. She never stopped dreaming of piloting. Fascinated of stunt flights and air shows she made her first solo flight in 1921. With the help of her mother she bought her own plane.

“Now and then women should do for themselves

what men have already done –

occasionally what men have not done –

thereby establishing themselves as persons, and perhaps

encouraging other women toward greater independence of thought and action.”

Amelia Earhart (1898 – 1937)

In 1932, five years after Charles Lindbergh, she was the first woman to fly the Atlantic. The Press dubbed her “Lady Lindy”, the female Charles Lindbergh – a questionable naming in consideration of Earhart’ s pretensions and from feminist perspective: men as reference point for the name of a woman.

After the first official flight competition organized for women in 1929, the “Women’ s Air Derby”, Amelia Earhart founded an organization for women pilots named “The Ninety Nines” (or: “The 99s”). Thus she smoothed the way for women in aviation and set a further step to take their piloting seriously. Many times they were derided and ridiculed as women pilots. Their transatlantic flight competition, for example, was called “powder-puff air-race”. By the way:The strategy to expose women to ridicule still is used as a general way to degrade females. In 1937 Earhart determined to do “just one more long flight” that ended up tragically. In a Lockheed Electra and with the navigator Fred Noonan she headed on an around-the-world course along the equator-line. On the most difficult part of the trip, from New Guinea to tiny Howland Island in the Pacific, the aircraft vanished. After an extensive air and sea search that failed to turn up any trace of them, Earhart was declared dead.

Every once in a while I encounter elucidating quotes while walking through the exhibition:

“I refused to take no for an answer.”

Bessie Coleman (1892 – 1926)

Reading these words I think by myself: What remarkable, persistent, determined and single-minded person must this lady be? Her name is Bessie Coleman (1892 – 1926), nickname “Queen Bess”, known as the world’ s first African-American woman aviator.

What sounds as easy as this, in real life meant a lot of hardship. She grew up in Texas as the tenth child in a family of thirteen. As a child she had to work in the cotton fields. Besides, she learned about aviation by reading. She was denied admission to American aviation schools because of her race and her sex. But she did not give up. She learned French, went to France and earned an international pilot’ s license at the highly respected “Federation Aeronautique International”. Back in her home country she could not make a living as a civil pilot. Therefore she was touring the USA to earn money by giving stunt flights and parachuting. As a courageous woman she also challenged the barriers of racial discrimination as she refused to participate in segregated events. Her idea to open an aviation school for African-Americans did not come true no more. In 1926 Coleman bought a new but defective airplane. Although her family and friends warned her to fly it, she did. In order to check the territory for her parachute jump the next day, she did not buckle up. Unexpectedly the aircraft side-slipped and she went by the board, 610 meters down – she died. With her work she cleared the way for “people of color” in aviation. To honor her, every year African-American pilots drop a wreath from the air over her burial-place.

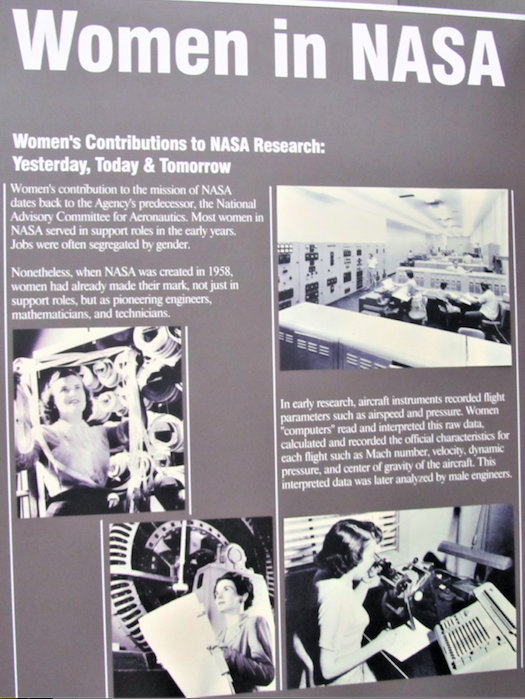

From these exiting stories about women in aviation I move over to another breath-taking field – women in aerospace. In the early years women mainly served in support roles. Beyond that they managed from the very beginning of NASA (1958) to work as mathematicians, engineers and technicians.(*) With their pioneering and fundamental calculations they cleared the way to the moon for NASA. It essentially is due to them that the Americans won the race to the moon (1969).

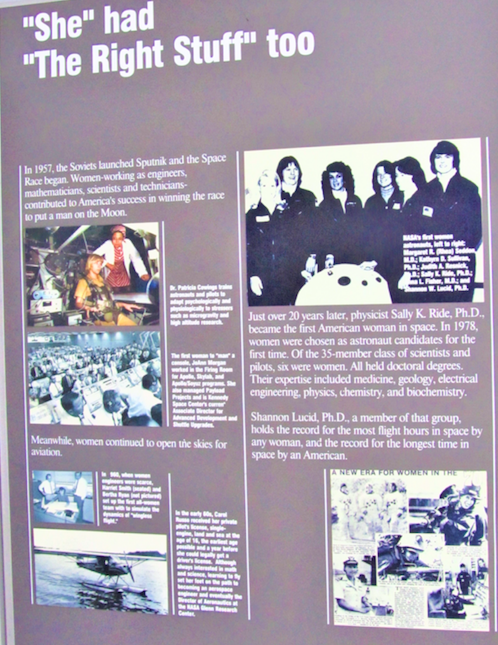

In 1977 NASA was looking for technicians and scientists who could monitor the complex technology of the space-shuttles. 8000 persons applied for the jobs, among them 1000 females. 35 astronauts were selected, 6 of them women. One of them rose to fame as she became the first American woman in space:

“I can ‘ t remember a single time

my parents ever told me

not to do something I wanted to do.”

Sally Ride (1951 – 2012)

She joined NASA as an astrophysician. She took part as a mission specialist on Space Shuttle Challenger 7 (1983). At an age of 32 she was the youngest person in space at that time. Before, the Soviet Union had sent the first women to space, the cosmonauts Valentina Tereskowa (1963) and Svetlana Savitskaja (1982). 20 years later Sally Ride followed them as the third woman in space. After a second flight she logged 14 days and 8 hours total in space. Her sex attracted attention to the Press and she was asked questions a man never would have to answer:

-

- Will the flight affect your reproductive organs?

- Do you weep when things go wrong on the job?

Although questions like these have not vanished yet, today the questioner at least exposes himself as sexist. In 1986 Ride was part of the commission investigating the Challenger explosion. To commemorate her the U.S. Postal Service has printed 20 million of Sally Ride Forever stamps.

After my visit I leave the museum inspired and with great respect towards these extraordinary and daring women. Being aware of the fantastic achievements of women in space, one would take for granted that today women may take part in space missions equally. By what does equality in space fail even in 2019? In details like suitable clothing, it gets obvious how deeply rooted patriarchal thinking with its role cliches nestles in our heads. Under the title: “Missing: space-suit” I read an article in an Austrian news-magazine (Profil, nr. 14; 31.3.2019) that the first mission outside the International Space Station ISS that should be conducted by two women, failed. The adequate space-suit, size medium, was missing. Instead of the second woman to accomplish a battery change, her male colleague slipped into the available larger model. The devil is in the “nuts and bolts” (not only in case he is wearing “Prada”) – even in the field of extraterrestrial gender equality.

(*)Margot Lee Shetterly: Hidden Figures (Harper Collins); filmed by Theodore Melfi: Hidden Figures

Written by: Marianne Wimmer, collector of women’s museums

Coming up next: Michigan Women’s Historical Center & Hall of Fame Lansing / Michigan