Known to everybody, even to those who have not yet strolled through it – that’s the no. 1 of China’s streets, Nanjing-Street, situated in the heart of Shanghai. It is Sunday, that means, thousands of people come along with me, go for a stroll through this well-known ‘hypermarket’, which ends up at the promenade “The Bund” at the banks of the river Huangpu. From here I enjoy a fantastic view on “Shanghais Manhattan” that stretches on the other side of the river. Afterwards I squeeze my way through the crowds of the old town of the metropolis. After these dense experiences I’m longing for a bit of more space around me, and above all, quietness. Contrary to my expectations both of it is offered to me in the “People`s Park”. Although well attended as well it feels like delving into a small oasis with a relaxing atmosphere. And – unexpectedly, I run into the Chinese marriage market. At first sight I am wondering about the scenery: a lot of opened umbrellas with texts glued to them, women and men sitting in between. Are they demonstrating for some reason? But everything looks very calm and relaxed. Later on I come to know that these people advertise their daughters and sons, they try to match them for marriage. With or without their children’s consent – that varies. Not all of them want to marry, despite the wish of their parents. Especially highly educated women with well-paid jobs nowadays prefer to live independently. And the ones who would like to wed often fail because young men still prefer to marry a woman with less education. Some agree with their parents in arranging a match because they themselves do not have time searching for a partner. It goes without saying that the young ones in China use speed dating and dating platforms as well. With their activities as matchmakers the parents follow a long tradition in China. Some days later I meet with this old practice and its ideas about beauty – in the women’s museum in X’ian:

With subway, bus and a bunch of helpful people it is no big deal to reach the women’s museum. In addition I stick to a method that proved to be successful for finding my way even 28 years ago, during my first trip to China: Let somebody who speaks English write down in Chinese letters the address of your destination, the name of the bus station you have to jump off the bus and show it to the bus driver – just in case if there are no signs in Latin letters. You will make it!

Safely and highly protected by a gallery of surveillance cameras, a guard included, I move through a turnstile at the access to the campus of the Pedagogic University. How many of such monitoring cameras have traced my way up to here?

In front of the building “Museum of Education“ two young ladies are already waiting for me to guide me through the exhibition rooms. With their help I obtain a general overview of the museum’s contents. Besides the tradition of footbinding, the Jiangyong Women Characters, life stories about women of various eras, the history of reproduction, products and techniques of needlework and a variety of traditional wedding costumes from all regions of China are further focal points of the museum. After my guided tour, accompanied by a script with English texts, that I get as a gift, I scrutinize the most interesting parts of the museum again.

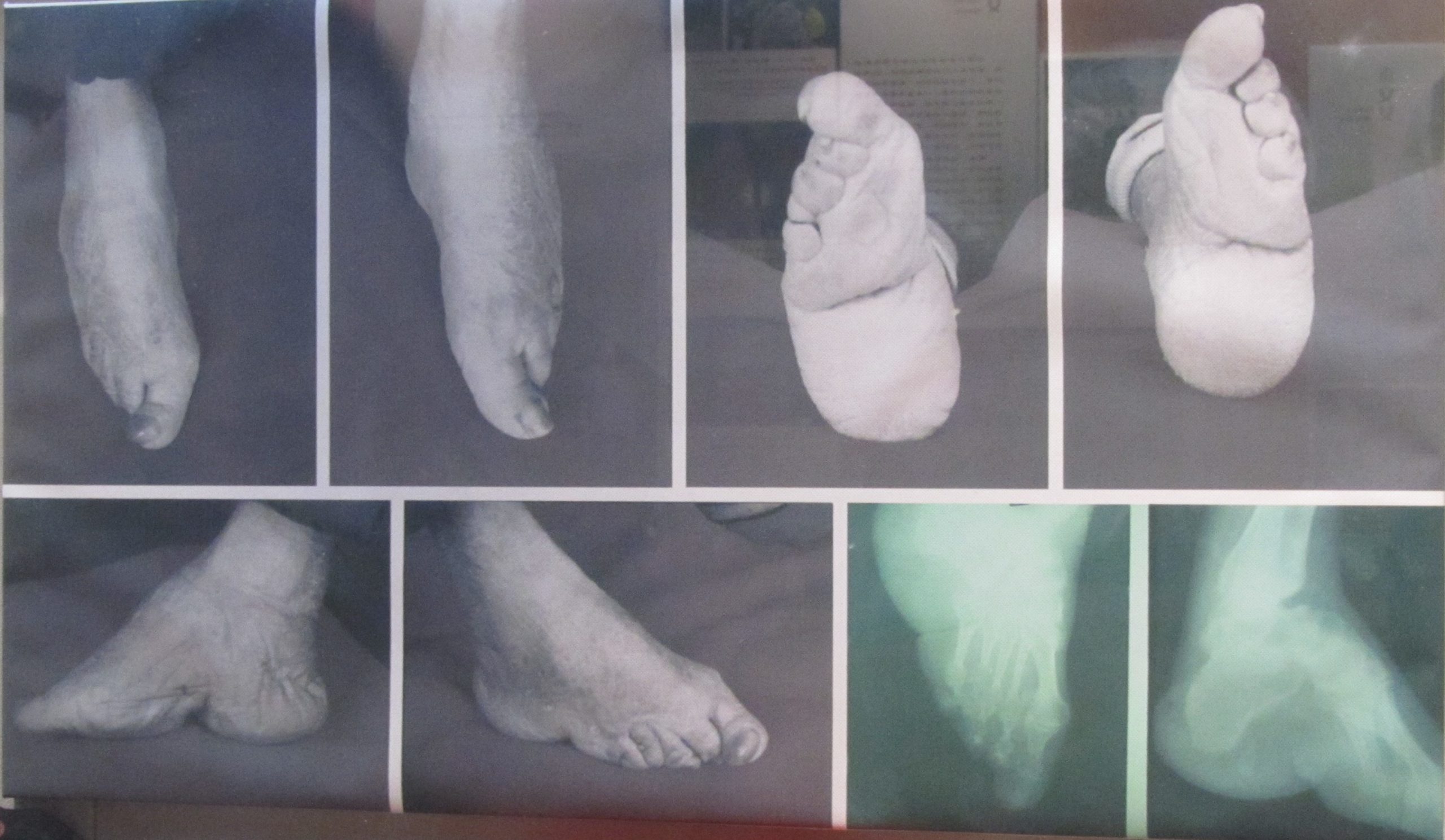

“What are your expectations?” With this question the two students put me into the proper mood for the following guided tour through the museum. As I mention the catchword ‘Lotus feet’ in my answer, we head to the first section of the museum.

Lotus feet to gain men’s favour

The smaller, the better are your chances at the marriage market. If your foot is not longer than 7 cm (as long as my ring-finger), you are the gold medal holder as a bride. Your foot not longer than 10 cm – it means you win the silver medal within this beauty contest. From 12 cm onwards your feet are characterized as “iron“ – no medal at all. It’s unbelievable – my eyes are wandering back and forth from the pictures on the wall that demonstrate the brutal way to reach this ideal, to the tiny shoes in the showcases and down to my 24 cm long feet. Thinking of the terrible pains that girls had to suffer, my face automatically is distorted by pain. At the age of 5 the torture began: deforming feet by binding and bandaging. Rivulets, no – rivers, no – streams of tears must have run down the girls’ faces during this yearlong brutal procedures, combined with infections, pus, bruises, stinking and rotting meat. Not all of them survived these tortures, approximately 10% died of sepsis. Although the first time forbidden in the 17th century, footbinding continued. At the time of Mao it again was forbidden but it was kept in traditional rural areas, at least on a smaller scale. My guides tell me that the last lotus feet were seen in the 1980s.

Some steps apart we step into a section of the museum I would define as ‘realm of propaganda’. It is obvious for me at first sight, when I look at the design of the showcases with its typical glorifying style, in this case devoted to “Mao and women”: Mao is presented as liberator of women and promoter of the equal status of women and men. It is safe to assume that Mao had a big influence on the social and communal life of the sexes. I am wondering about the fact that the museum only points out his prohibition of foot-binding but not the one concerning polygamy or forced marriages. Mao was convinced that women should choose their husbands themselves and to be able to file a petition for divorce. In the center of interest stands his slogan “Half of the sky”.

He wanted to emphasize that in contrary to old China, when men were regarded as the sky and as masters of the world, women can do everything as men can do. After the 2nd World War, in the 1950s, during the newly founded People’s Republic of China women got any kind of work. They were encouraged to engage even in hard labor like well- or road building. In contrary to China’s strategy, the museums texts mention that “the developed countries encouraged women to go back home in order to relax the tension of men’s asking for jobs”. The other side of the medal is missing in the museum – no word about the fact that women now had to bear the burden of household work and job requirements. In addition they should work for the revolutionary communist party. What about the second “half of the sky” for men? Mao apparently did not say anything about that. Examples for the heavily impact of Mao’s Cultural Revolution even into very personal realms may be seen under the title “The Red Embroidery”. The revolutionary needlework, like embroidered images of Mao, was very popular. Another example for his big influence on personal things was that he forbade women to wear women’s dresses. What am I missing? I cannot find any hint on Mao’s terror regime with its millions of dead people. For sure, women had to tell many stories about that.

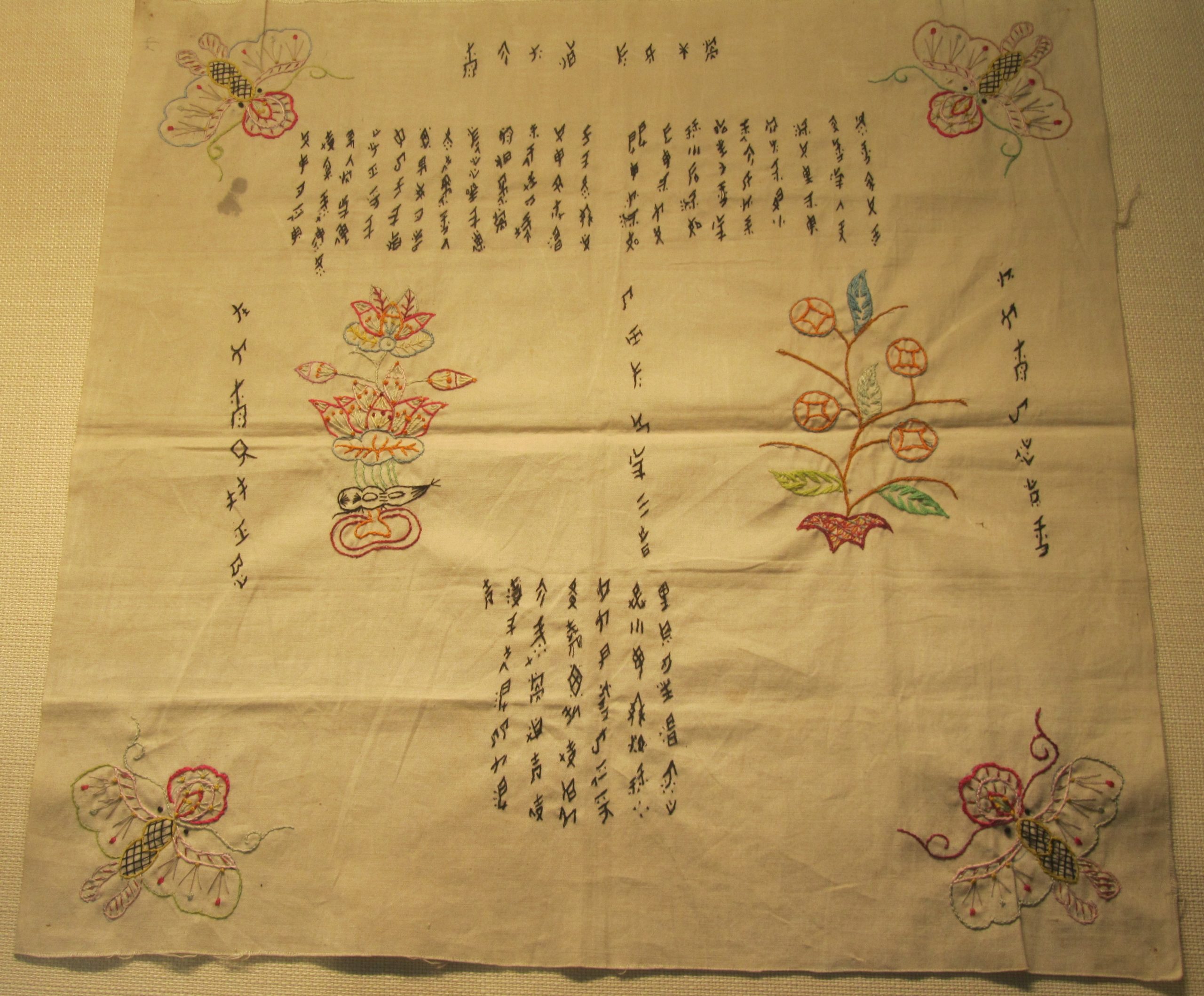

Women’s solidarity mirrored in secret writing

Curvy, slim, rhythmical – no horizontal and only a few vertical lines like Chinese writing used it, but a lot of slanting letters – that is how the letters appear in the secret cipher that was developed by the women of the Jiangong region, in the province of Hunan. What is hiding behind this conspiracy of the daughters of Eve?

In general a blood sisterhood consisted of 7 members of all ages, origin, decent or social status. Women who felt congenial in thoughts or wishes, who had a special liking for the same things gathered in a group. They promised to support and care about each other during their whole lifetime, like real sisters. If they sent messages to each other they had to be written in their secret writing and only delivered by women. In many letters they expressed their displeasure about their weak social status, the bad reputation of women in society and the hard life as a result of it. They used the letters to console each other, to ease their hardships by complaining, expressing their sadness, by receiving conciliating words from their “sisters”. They need not be in fear that their husbands would come to know because of the encoding. They put these secret writings on paper, on fans, on handkerchiefs or in beautiful thread-bound books.

Besides the letters they wrote poems, songs, ballads, prayers and hymns and even their oaths of sisterhood. A special and very interesting form were the “Wedding Laments” and the “Wedding Congratulation Letters”, made of precious material. They were given to the bride on the third day of the wedding ceremonies. In between the thread-bound book, the bride would find the wishes and hymns on her person, followed by blank sheets of paper. After the wedding the wife could write down her thoughts about the marriage and her new life. Many times they put down lamentations. How come? Many young women were reluctant to get married and expressed their dislike and resentment towards marriage. In her parents’ family she often lived and enjoyed a happy life with much freedom. Once she got married she had to live in her husband’s family, which often meant suffering and being restrained.

Women learned from their mothers or other elderly women how to write and read a secret letter. Only a few of them got experts in it. They could create and rewrite poems and articles. Thus, the writing was done by those who were good at it. These women were highly respected within their communities for the important role they played. Works of secret writings seldom were passed down from generation to generation. As women believed in the nether world most of the works were buried as funerary objects or burned up.

Taboo: Sexuality

Did the sworn sisters talk about sexuality, about its pleasures or did they pour out their troubles to each other? The text I am confronted with in the section of the museum that deals with “Reproduction -Childbearing – Menstruation – Abortion” opposes it and for me it sounds like it still applies today:

Different from the Western tradition, the Chinese people never write the teaching of sex on paper or say something about it face to face. Instead, they use some things to suggest what they should do.

The remarks on sexuality of today in the book “Daughters of Mulan”(*) seem to confirm the text of the museum. Have a closer look at this exquisite and vivid art work, made of bones, on the photo.

When folded it looks like a harmless fish, when opened you may study a couple engaged in sexual activities. When their daughter gets married, the parents put this special object into her suitcase to inform her how the sexual intercourse of a couple may work.

Besides menstruation, birth and fertility rituals you get an insight into contraception and abortion. Opposite the artefacts that were used when praying for children, a piece of wood, carved from top to bottom with letters, displayed in a showcase, attracts my attention. It is a block for printing from 1911. The title “Admonishing against drowning baby girls” reminds me of the “One-Child-Politics” in China, from 1979 – 2015. As a result of it many first-born girls were exposed or killed, in order to get the chance to procreate the yearned male offspring at the second attempt. But here I come to know that girls were of small value already for centuries. From an economic perspective they were seen as ‘cost factor’ compared to boys that had the image of being a ‘pecuniary resource’. It is worthwhile to read the text, even if it is not nice for women. The author, Cheng Zixing, a scholar of the Qing-Dynasty (1644 – 1911), opposes against the corrupt costumes of killing babies. He wants to persuade people to respect life: ”The baby girls of today will be mothers tomorrow. Mothers giving birth to baby girls are the ones who have not been drowned as daughters……How can you ruthlessly drown your own flesh and blood in the basin; and how can you brutally see your daughter do her last breath without any move;…“. From history we know that it is very important, especially for women, where and when on this planet they were/are born. I realize that I had great luck to be born in Austria. Born into a farmer’s family my father was not fond of me as his second-born female offspring. Later on my mother told me that he did not want to take me home from the hospital, because he was longing for a male heir. As the second-born girl I was a big disappointment for him. But, at least, I never was in danger to be killed for having the wrong sex. In those regions in China, in which only two kids were allowed, second-born girls had to be afraid of being killed, if they already had a first-born sister. Nowadays, there are 24 million men more than women living in China. Many of them cannot find a wife and so they fall back upon practices that Mao already forbade. Newspapers tell that there exists robbing or kidnapping of women from neighbouring countries. Others try to recruit women from other Asian countries. Although the One-Child-Policy was ended in 2015, the birth rate in China is as low as at the beginning of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. It is very impressive to look at the numbers that express that fact: 14,6 million babies were born in 2019, 500 000 less than 2018.

To get rid of all these bad facts about women I again go to the section of “Needlework”. In Chinese traditional society women rarely had public activity space. So they used their creativity within their homes. In this world of female culture exhibited here I admire impressive paper cuts, weaving works and embroidery and – very special for me, as I have not seen them before – the imaginative creations made of dough. They are given as gifts for special occasions, creations for girls and boys for the Chinese Valentine’s Day, for the groom and the bride or for the birthday of seniors, to wish them longevity

Marianne Wimmer, collector of Women’s Museums

Previous article: Visiting the ‘comfort women’ museum in Taipei

Coming next: China National Museum of Women and Children / Beijing, CHINA

* Bettine Vriesekoop: Dochters van Mulan (first edition), Uitgeverij Brandt; Amsterdam.

German edition: Mulans Töchter, Pirmoni Verlag; Krefeld, 2018